EcoBambu

Written by Lindsy R. Glick

Artisan Association

Outside the humble cement building of EcoBambu, the sun beats down on the ground, covered with near-perfect grey rectangles of thick, textured paper. These water-logged squares have been draped over the fence, spread on the cement, stuck to the walls, and laid on the grass. Even without entering, it is clear that the building is a paper factory. Below the drying squares of paper on the walls are stacks of old newspapers, boxes of magazines and printing paper, cardboard and scraps--all waiting to be torn to shreds and reincarnated.

At the entrance an old, weathered man sits on a stool and slowly, methodically tears 8 ½ x 11 papers into halves, fourths, eighths…and drops them into a bucket at his feet. He is the only man in this bustling, damp building, water seeping to the drains from every corner of the room. His hands are curled, and only one of his eyes focuses fully on its target.

At the entrance an old, weathered man sits on a stool and slowly, methodically tears 8 ½ x 11 papers into halves, fourths, eighths…and drops them into a bucket at his feet. He is the only man in this bustling, damp building, water seeping to the drains from every corner of the room. His hands are curled, and only one of his eyes focuses fully on its target.

Across from the old man is a long, wooden table where five women work with the dried, pressed paper. One is measuring and trimming edges, one is making lines and creases, one is cutting patterns, one is folding, one is gluing. These women talk and laugh, pausing their work to lay a hand on one another in empathy. Sometimes their gaiety shifts to solemn topics and the woman comfort and console each other in the loss of a loved one, the pain of seeing a friend addicted to drugs, or the bruises they bear from angry husbands. No matter the topic, though, these women have bonded well, and their days pass without heed to the clock.

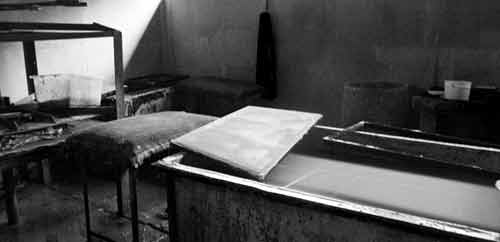

Women not sitting at the table are part of this intimacy as well, and it seems that jobs shift throughout the day; their skills almost entirely interchangeable. Other tasks include pouring buckets of saturated paper scraps into a blender and large basin for mixing. Two women lift paper onto a form and let water soak through the screen. Each of those screens is then pressed using a large, archaic-looking crank with four long handles attached to the axle. This torque extracts the majority of water content from the screen of paper. The rectangle is then removed from the screen and placed between cloths for further pressing. After being run through a large wringer, each rectangle is hung from clothespins on a line near the ceiling or adhered to a wall. Some are placed directly outside to dry.

The building itself is a physical and figural landmark for the women of Ecobambu, signifying the triumph of many struggles and the complications of beginning an association. The women spent long hours dedicated to the development of their dream, applying for grants, soliciting donations, and traveling four hours by bus to the capital, San José, to buy equipment. They received land from a Monteverde scientific research center, but still faced the challenge of mortgages and salaries.

Ecobambu was formed with several explicit

goals. Helping the environment was key in this project. All office paper, cardboard and newspaper used to make new paper are waste. It is trash that others throw away, or extras that will not be distributed. Not only does this transform trash into beautiful products, but it also saves many truckload trips to the larger town below to deliver trash to the landfill. By coloring paper with plant and flower material, Ecobambu avoids chemicals, soaps, or dyes in the their paper, which means that they avoid dumping harmful substances into the earth at their feet.

Ecobambu was formed with several explicit

goals. Helping the environment was key in this project. All office paper, cardboard and newspaper used to make new paper are waste. It is trash that others throw away, or extras that will not be distributed. Not only does this transform trash into beautiful products, but it also saves many truckload trips to the larger town below to deliver trash to the landfill. By coloring paper with plant and flower material, Ecobambu avoids chemicals, soaps, or dyes in the their paper, which means that they avoid dumping harmful substances into the earth at their feet.

The other major goal in the formation of the association was to create employment opportunities in the community, especially for women. It was and is important to the founders of Ecobambu for women to have the option to work outside the home, to feel a pride in their work, to be productive, and to help support the community.

Both goals have clearly been met. One explains, “I never thought I would be an important person in a group like this. I was just a normal person, working in the house.” This woman began working with Ecobambu in her sixties. She says that she is old, but not useless. She does not wish to leave her community, and it feels good to work, make things with her hands, to contribute. At her age, she says, the work is like a therapy, and she likes feeling that people need her.

Another woman, married with five children, says that she had always been such a shy, quiet person

who stayed in the house. Since starting work at Ecobambu, she knows more people in the community, and actually leaves the house to visit friends. She is more economically stable and is able to contribute to payments for electricity and supplies at home. It gives her great joy to make her own money, and people notice how much she has changed since becoming a part of this group.

Another woman, married with five children, says that she had always been such a shy, quiet person

who stayed in the house. Since starting work at Ecobambu, she knows more people in the community, and actually leaves the house to visit friends. She is more economically stable and is able to contribute to payments for electricity and supplies at home. It gives her great joy to make her own money, and people notice how much she has changed since becoming a part of this group.

Such stories do not always come without conflicts as well. Many of the women anger their husbands by leaving the home to work. Some give up working. Some end up getting divorces. Others deal with domestic abuse. And it is almost always true that even if the husband approves of the woman working outside the home, she is still responsible for all household chores and must cook, clean, care for the children, and do laundry early in the mornings and each evening after a full days’ work.

These incredibly strong women, though, find their experiences with each other and the pride in their work well worth the time and energy spent to make their handicrafts. Their completed bags, notebooks, journals, photo-books and boxes decorate a glass-cased shelf. Most products, though, are not sold directly out of the factory but are sold through tourist shops in Monteverde and Santa Elena. The women are learning to paint and embroider small birds and flowers native to their area on the books and bags. The colorful additions are reminders of the things these women will continue to learn.

At the end of each day, the women remove their rubber boots and aprons, tidy up their small, wet factory and close and lock the large double-sliding doors to their success as an association, a support group, employment, and paper factory. Tomorrow they will open those same doors, greet each other with kisses, and commence the day with new stories and new energy. And they will continue to transform old, thrown-out paper into beautiful, homemade products, with pieces of dried flowers and pieces of their lives engrained in each rolled, trimmed, perfect rectangle.