Return to Costa Rica

Written by Beth Martin Birky, 2008

It’s been almost seven years since I returned to Costa Rica as a feminist. That’s an odd distinction to make about international travel: pre- and post-feminist. And honestly, I cannot clearly identify when I made that shift.

When I left for Costa Rica SST (Study-Service Term) in January 1981, I gave little thought to the way being a woman would shape my international experience. Now having taught Women’s Studies courses since 1992, I recognize the cultural narrative I was living out as a twenty-year-old, white middle-class female from the U.S. In spite of my ignorance, I learned a lot about Costa Rican history, about valuing cultural difference, and about identifying my own limited cultural lens. But I am sad that I asked very few questions about women’s experience in Costa Rica’s peaceful but machista culture.

When I left for Costa Rica SST (Study-Service Term) in January 1981, I gave little thought to the way being a woman would shape my international experience. Now having taught Women’s Studies courses since 1992, I recognize the cultural narrative I was living out as a twenty-year-old, white middle-class female from the U.S. In spite of my ignorance, I learned a lot about Costa Rican history, about valuing cultural difference, and about identifying my own limited cultural lens. But I am sad that I asked very few questions about women’s experience in Costa Rica’s peaceful but machista culture.

In 2001, I began asking questions when my husband and I led Costa Rica SST. I found it difficult to overlook women’s issues: domestic violence, teenage pregnancy, husbands with two families, machismo. But I also learned about Costa Rican women’s unique opportunities: a high level of education, access to good health care, supportive labor laws, government-mandated 40% female candidates for every ballot.

In the past seven years, as I’ve returned to Costa Rica four times to research women’s organizations, I have learned how essential solidarity and collaboration are to women’s organization and empowerment in any community.

I don’t hear very much about collaboration, solidarity, or compassion in the U.S. women’s movement these days, and I think we are the poorer for it. Costa Rica’s average annual household income was $13,500 in 2007, while the World Economic Forum’s Gender Gap Index (GGI) ranked them 16th/128 countries for women’s overall political empowerment. In comparison, U.S. households averaged $46,000 and received a GGI rating of 69th/128. What contributes to those differences?

Many U.S. feminists focus on freedom of expression, sexual identity, and equal rights. Most of us unconsciously adopt a feminist version of U.S. individualism, the “pull ourselves up by our [high-heeled or hiking] boot straps” ethic. In Costa Rica, however, community is valued highly.

I remember one San José woman’s comment about watching her neighbors struggling to find work, to pay the rent, and to clothe their children. She asked herself, “How can I be doing well if my neighbor is not?” She believed that she must not only work for herself and her family’s security; she also had to take care of the people around her in order for her community to thrive. That was the birth of her neighborhood women’s association.

I remember one San José woman’s comment about watching her neighbors struggling to find work, to pay the rent, and to clothe their children. She asked herself, “How can I be doing well if my neighbor is not?” She believed that she must not only work for herself and her family’s security; she also had to take care of the people around her in order for her community to thrive. That was the birth of her neighborhood women’s association.

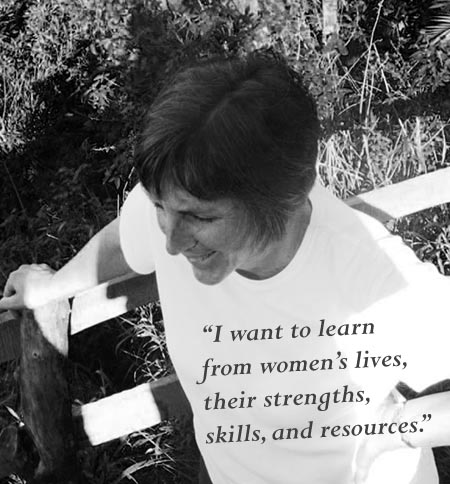

As a feminist scholar doing research and teaching in an intercultural setting, I want to learn not only about women’s lives, but also from them, from their strengths, their skills, and resources. I want to apply those lessons in my own community. What needs do women have in a Goshen trailer factory, a local business, in my church, or here on campus? How can women collaborate, support, and empower each other? If we care about the questions and care about each other, we might be surprised by the answer.